It’s that

time of year when we tend to think about and express our gratitude more often than

usual. We are grateful for the love and support of family and friends, for good

health, food in the cupboard, for kindness and understanding from others. We

also tend to be more generous this time of year, serving a meal at a shelter,

dropping money in the kettle of the bell ringers, or writing a check to a

favorite charity. We certainly hope our museums will be on the receiving end of

others’ generosity with a year-end gift.

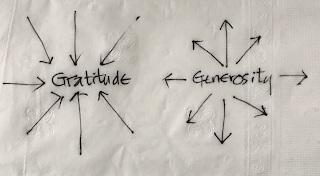

While

valuing both gratitude and generosity, I’ve

gradually decided

that gratitude is relatively easy; generosity takes work. Generosity, it seems, is a more demanding, active, and

compassionate form of gratitude. With gratitude someone else’s generosity or a

lucky moment has enhanced us. We feel grateful to be on the receiving end of someone’s

good will, gift, attention, or extra effort. How hard is that? On the other

hand, when we have given up time, wisdom, or money, our generosity enhances the

situation or wellbeing of someone else, not ourselves. Generosity is our giving

without the expectation of someone else’s gratitude.

We are

likely to think of people like Bill and Melinda Gates when we think of being generous.

There is a link between generosity and resources with a long-standing

connection between generosity and the elite. In fact, the origin of the word generosity is from the Latin word

meaning of noble birth.

We don’t,

however, need to be rich to be generous. True generosity is the quality of

giving good things to others freely and open-heartedly. We can be generous with time, attention, advice, donating our

body’s blood or organ, patience, kindness, hospitality, mentoring, money, or service

to others. Everyone,

even very young children and people with seemingly few resources can be

generous to others.

Generosity

is a disposition to do well towards others. As an inclination to act in a certain

way, generosity is something we can all practice. While it takes more time and

effort than a polite thank you, we

can all do an errand for someone else, let someone get ahead of us in line, and

remember the anniversaries of loss and suffering. We can live in generous ways

in everyday moments, giving more than we think we have to give, sharing more

than may feel convenient, or giving what’s needed with respect.

Giving is both an individual

and a social act. When we give, we are contributing in some way to others in a

social network, to our neighbors, members of our congregation, someone we

tutor, a homeless family receiving a meal, or refugees living in a camp on

another continent. The act of giving connects us to others and contributes to a

stronger social network that may be small and near, or distant and large.

It might sound like a

Hallmark greeting card to say that generosity gives twice–at least. Our

mentoring, financial contribution, time listening, or doing a favor contributes

to someone else’s wellbeing. In return, these actions refresh what we have

allowing us to recognize our capabilities, enjoy a sense of purpose, or

appreciate that we are in a position to give. Giving further serves our

enlightened self-interest and how we see ourselves.

Of

greatest interest to me is a generosity

of spirit, giving that depends less on the money we have or the opportunities

and privilege we have received from others. In that sense, it is more available

to more of us and with fewer limits. Having money to act on behalf of others or

in the interest of our community is not required.

Although generosity

does not necessarily beget generosity, it does spread good will, redistribute

advantages, and create openings for change. When museums cultivate a spirit of

generosity within themselves in addition to encouraging supporters to give time and money to

their missions, they create larger openings that invite and inspire people and ideas.

Along with playing a valued role

in their communities, museums’ generosity can help strengthen communities.

Museum resources like spaces can be meeting places, event spaces, or even

platforms for friends and partners to support their friends and partners. Museum

expertise in problem solving, event planning, or creating interactive

experiences can help community groups meet their goals, and not just advance

those of the museum. Helping partners

meet their goals makes stronger partners and a stronger community.

The

museum field is a generous field. We share ideas and lessons learned about what

worked and didn’t. I know this first hand. Without the

generosity of strangers in museums who became friends and colleagues, I would

not have managed to start a museum, expand a museum, help museums grow, or

write a blog. Such helpful, generous guidance from so many is a model for me and for others to make introductions, share resources, and give away ideas. Because any idea is inspired by the generosity of others sharing their

ideas, what they have seen, heard, and thought before, giving away ideas

provides others with fresh ideas for their thinking.

In our

museums and professional service groups, a generous spirit helps

build a culture of respect and acceptance. This spirit allows us to give someone the benefit of the

doubt, tolerate ideas and behaviors that may be at odds with our own, listen to

someone with who we disagree as if they might be right.

This act could inspire someone to go out of their way for someone who needs something, not expecting anything

in return.

Gratitude

is appreciating life’s gifts. Generosity is sharing life’s gifts. We need gratitude. But we are diminished without generosity. We

could probably survive as a species and a society if we didn’t feel and express

gratitude. There would, undoubtedly, be consequences of not hearing someone

say thank you, or not opening an

envelope to read heartfelt thanks. We could not, however, survive without

generosity of spirit, open-hearted sharing, and true giving.

Of

course, acting generously does not, for a moment, mean not feeling and

expressing gratitude as well.