|

| New views on learning together (Dalston Mirror House by Leandro Ercich) |

When we think

about learning together in museums, we note that museums are social spaces. We

focus on visitors as part of groups, small intergenerational social groups–families–and

school or community groups. We plan for learning in such groups in exhibits, on

tours, and in structured program activities.

While the

group is a powerful context for learning in museums, learning together also

occurs in ways that are not necessarily visible, within a group, or planned.

Adults

and children; first-time visitors, seasoned members, staff and volunteers;

people in groups and exploring solo are each likely to be learning together. That’s

not surprising. This is how we learn. Beginning with the finely tuned

interactions between mothers and infants, we build meaning together through

social interaction. David Hawkins, referencing Vygotsky, Dewey, and Malaguzzi,

stated there’s never learning that is not socially constructed.

Because we

do make sense of our world through interactions with others, we are often

learning from them informally through conversations, gestures, and observation.

In a gallery this may be a visitor noticing how someone handles a tool or refolding

a paper airplane after watching how another paper plane floats down. It may be

a docent learning from a tour member’s question or someone eavesdropping on a

conversation about a painting on view.

The ideas

we pick up from others and build on are part of learning together and critical

for us doing our jobs. Someone’s stickie note posted on the talkback board may spark

an idea for an idea for an exhibit activity. The grant proposal you are writing

or the conference session presentation you are working on is your learning

together with colleagues. Without learning from others’ well-framed question, study

results, or trenchant observations, my blog posts would consist of a few

phrases and some examples.

Learning

together is not the same as getting people together in a group with an

intention for them to learn from a given agenda. Just being together in a

public lecture, at a staff training, or at a funder’s gathering of grantees to learn

about its projects does not necessarily involve learning together.

A working

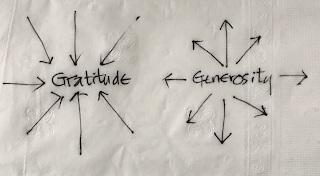

definition for learning together might be the active, co-exploration among informal

learning partners to make meaning through watching, listening, talking, or

gesturing. These learning partners may, or may not, be obvious, known to one

another, or even present.

A visitor

engaging with an exhibit might be inspired by seeing how someone uses their

body to lift a heavy object; from noticing the features of an elaborate block

tower created and left by others; or from observing a technique for working

with a new material. Nearly hidden as these moments are in the flow of words

and movement at an activity, in front of a fish tank, tapping on a screen, learning

together is learner driven, on-the-spot, and occurring before our very eyes.

And they happen in a flash.

Learning together in the Zone of Proximal

Development

For

instance, we sometimes see a child pair up with another child or call on an

older partner to work with on an activity or solve a problem. Bringing together

different levels of information, skills, interests, and experience expands the available

range of capabilities, of sense making and meaning making. These interactions

produce new learning and insights such as, “Oh! I see how to do that now.”

Learning is occurring through what Vygotsky calls the Zone of Proximal

Development, the difference between the actual and potential level of

development available through collaboration with a more capable peer.

For

instance, we sometimes see a child pair up with another child or call on an

older partner to work with on an activity or solve a problem. Bringing together

different levels of information, skills, interests, and experience expands the available

range of capabilities, of sense making and meaning making. These interactions

produce new learning and insights such as, “Oh! I see how to do that now.”

Learning is occurring through what Vygotsky calls the Zone of Proximal

Development, the difference between the actual and potential level of

development available through collaboration with a more capable peer.

• When museums create collaborative experiences and

activities that invite a wide range of capabilities, skills, knowledge, and previous

experience they support learners in benefitting from more capable or

knowledgeable peers and enhance meaning making.

Just-in-time information pertinent to the moment

In the

lively mix and mingle that can occur around a display case or an exhibit

activity several conversations may be murmuring along at one time. Anyone

nearby might overhear someone’s excitement about what they are looking at, hear

an explanation of how something works, or pick-up on the significance of a tiny

detail. At that moment, the learner gets something they would be unlikely to

get otherwise: just-in-time information pertinent to the moment, the place, the

activity, and what’s going on. Not everyone leaves with the same understanding,

but each does have a relevant understanding of their own

• Museums can add to the richness of visitors’

explorations and inquiry by facilitating opportunities for conversation in spaces

where people can bump into one another, work or stand side-by-side, and

eavesdrop. Something fascinating to notice and talk about in places to linger also

encourage conversation.

A dialogue through the medium of materials

|

| Photo credit: Spielgaben.com |

Two

children work side-by-side exploring clay at a worktable. One child looks at the

other child’s clay construction, a construction with wires. Noticing the wires,

the child adds wires to their construction. When the other child sets a piece

of fabric on top of the wires, the other does as well. That child then

carefully presses one shell and then several more into the clay and announces

that this is treasure at the bottom of the ocean. At first we may be inclined

to view this dynamic as one child copying from another. That moment when one

child glances at another’s choices and process to shape and elaborate a piece

of clay may be a dialogue between them through the medium of a material.

• Museums can support back-and-forth explorations by

creating places to work side by side with easy visual access that allows seeing

what someone else is doing. Offer a wide range of materials that prompt rich,

new dialogues. Mirrors mounted overhead showing what’s happening from a

different perspective provide additional opportunities to borrow, expand, and

learn together.

Revisiting what we have heard others say

In an

out-of-the way spot, someone sits alone in relative stillness. Waiting for

someone? Seeking quiet time? Enjoying a moment of reflection? In what may appear to be a solitary moment, someone could be considering

any one of a number of things: the light in this space, the source of light in a painting the docent noted,

and echoes of others’ comments about changing light and shadow. One

of the processes that occurs in museums is reflection, through which we learn. In reflection we revisit something we have experienced, something we

have heard others say. We continue the conversation through our silent inner

speech; remembered voices of others enter our thinking.

• To support reflection and internal conversations that build

connections and understanding, museums can create quiet spaces with comfortable

seating, and views that engage and calm.

Even when

we are exploring an exhibit by ourselves, we are not alone. In fact, we are

likely to make connections between what we are experiencing and what happened

previously and with others who are not present. We interact with the artist when we think about what we see

in a painting, even if it’s a silent, “I don’t get it.” We transport a strategy

we saw someone else use and apply it to another situation. Reading and

responding to a question on a text panel is a silent conversation with the author,

unknown to us, who composed the question. We may share our experience later

with someone over coffee.

• Museums support connections with others across time and

space by asking questions, offering suggestions, creating challenge and

uncertainty…in text panels, through staff engagement, through discrepant

objects. These and other strategies encourage learners to make multiple

connections that are meaningful physically, with others, and with previous

experiences.

Everyone learns something different together

Sometimes

a group of visitors spontaneously becomes a team working together at an

exhibit. They create a challenge or invent a problem they must solve together

and organize themselves around the challenge. It may be to move blocks on a

crank-operated conveyor belt from one level to the next in record time.

Commands come down to crank faster, updates are issued on how time is ticking

away, tasks are added to the challenge, new workers are added to cause, and

materials are adapted. In these moments, everyone learns something different together.

• Connected experiences, ones that flow physically, that

work with varying numbers of visitors and allow visitors to assume different

role support self-forming groups of visitors directing their experiences and

learning together.

Learning

together makes possible what might not otherwise occur. No amount of planning

on the museum’s part could provide the on-the-spot support or information, the

extra pair of hands, or the just-in-time idea that makes learning together

happen.

What new possibilities about learning

together in your museum do these examples suggest?